By Stephanie Hess, Northfield-Rice County Digital History Collection, January 2019

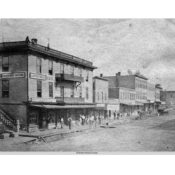

On the morning of September 7, 1876, the people of Northfield had no idea that their First National Bank was the target of the notorious James-Younger Gang. They went about their business believing their money, and their town was safe.

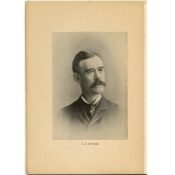

The James-Younger Gang had spent 10 years robbing banks, stagecoaches, and trains after the end of the Civil War. Confederate veterans Cole Younger and Frank James led the gang. Cole’s brothers Jim and Bob Younger and Frank’s brother Jesse James were the core members of the gang. On this day, Clell Miller, Bill Chadwell, and Charlie Pitts also joined the James and Younger brothers.

Why did these Missouri natives come to Minnesota? Minnesota was far away from their homes and the authorities would not look for them there. They had friends and allies who lived in the Twin Cities. Some gang members may have thought banks were easier to rob in Minnesota. They also still resented the people and prosperity of Northern states after the Civil War.

Whatever their reason, the James-Younger Gang was in Minnesota that summer, looking for new targets. Scouting parties of 2-3 gang members cased a few other banks before committing to Northfield. Their first choice was the First National Bank of Mankato. At the last minute, the gang became nervous about all of the people on the streets around that bank, so they left Mankato and headed for Northfield.

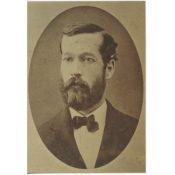

At around 2:00 p.m. on September 7, 1876, Frank James, Charlie Pitts, and Bob Younger entered the First National Bank of Northfield. They jumped over the counter and ordered the bank employees to open the safe. Joseph Lee Heywood, the acting cashier, replied that the safe was on a time-lock and he could not open it. In reality, the lock was open during business hours and Heywood could easily have opened it for the robbers, but he refused. He continued to resist the gang, even when they threatened and hurt him.

Heywood’s act of bravery gave the Northfield townspeople time to organize against the gang. The last customer to leave the bank before James, Pitts, and Younger entered was local hardware merchant J. S. Allen. When he realized the bank was being robbed, he sounded the alarm by shouting, “Get your guns, boys, they’re robbing the bank!”

In response, local citizens like Henry Wheeler and Anselm Manning grabbed whatever guns they could find. They began shooting at the rest of the gang guarding Division Street. In the chaos, Wheeler killed Clell Miller from an upper-level window across the street. Manning killed both Bob Younger’s horse and Bill Chadwell from behind the Scriver Building’s corner staircase. Bank employee Alonzo Bunker tried to escape and was shot in the shoulder, but he survived to provide an eyewitness account of the raid. A townsperson named Nicolaus Gustafson was caught in the crossfire and died several days later.

But the greatest sacrifice of the day was made by Joseph Lee Heywood. Frank James, furious about the turn of events, turned and shot Heywood in the head as he left the First National Bank. Then the surviving robbers escaped town at 2:07 p.m. with only $26.70 in spare change—much less than the $15,000 safely stored in the bank’s vault.

Volunteers from the Northfield area chased after the outlaws for two weeks. At some point in their escape, Jesse and Frank James separated from the Younger Brothers and Charlie Pitts. Because of this, both men escaped capture and returned to Missouri.

A posse finally caught up with the rest of the gang on September 21, 1876. At the Hanksa Slough near Madelia, members of the posse surrounded Cole, Jim, and Bob Younger as well as Charlie Pitts and forced them to surrender. Charlie Pitts was killed in the shootout and the Younger Brothers were captured. They pleaded guilty to the murder of Joseph Lee Heywood and were sentenced to life in prison.

Joseph Lee Heywood became an overnight hero for his loyalty to both the First National Bank and also his fellow Northfield citizens. He understood that the lives and livelihoods of his friends and neighbors depended on him. There was no insurance in banks in those days. If the James-Younger Gang had succeeded, the money would simply have been gone. It is possible that the 20-year-old town—including its two colleges—would not have survived.

Nearly 1,000 people attended the funeral of this otherwise ordinary citizen whose actions made him into a hero. Together with Henry Wheeler, Anselm Manning, and the other defenders of Northfield, Joseph Lee Heywood put an end to a decade of terrorism caused by the James-Younger Gang.

Primary Sources

Discussion Questions

When you look at the individual items in the Northfield History Collaborative, use the zoom-in tool to view details in the images or more easily read the documents. Use the tab labeled “TEXT” to read full transcriptions of the documents.

Questions

- A week before the raid, Carleton College president James Strong asked Joseph Lee Heywood if he would ever open the safe for robbers. He said, “I do not think I should” – in other words, NO. When the James-Younger Gang came, did Joseph do what he had predicted? What would you have done in his place?

- There were many people on the streets that day. When J. S. Allen raised the alarm, some people picked up weapons (including rocks!) and fought back. But others ran away. What might have motivated these people to react in such different ways? How would you have reacted? Would the raid have gone differently if even one person had acted differently that day? How?

- Many people saw what happened that day, but some details in their eyewitness accounts differ. Why do you think it is? Are any of these accounts more valid than others? How does this affect our understanding of the event?

- Take a look at the Rice County Journal’s front page from September 14, 1876 to read the local newspaper’s story about the raid. Then check out another newspaper’s story about the raid, like the Minneapolis Tribune on September 8, 1876, or another example from the Library of Congress’s page. How are these articles similar? How are they different? Do you understand this historic event better when you read more than one version of the story? Why or why not?

- On September 21, 1876, a teenaged boy named Asle O. Sorbel met the outlaws near Madelia, MN. He realized who they were and walked several miles to tell the authorities they were in the area, even though his parents told him not to (they were worried about him getting hurt). Read Sorbel’s account from 1924 and imagine you were in his shoes. How would you feel to run into outlaws who were wanted for crimes all across the country? Would you have disobeyed your parents to report on the gang? Why or why not?

- The posse that finally caught the gang was called the “Magnificent Seven.” Why do you think that is? Why do we know less about them than the gang they caught? Do you want to know more about them? See what else you can find out.

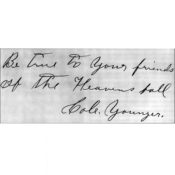

- Cole Younger’s note was written after a lawman asked him who really killed Joseph Lee Heywood. At first glance, it shows that Cole was a loyal friend who would not accuse other members of his gang. But if you think more about it, he was also protecting someone who had murdered an innocent man in cold blood because he was angry he couldn’t rob a bank. Can both of these statements be true? How does that affect your idea of the kind of person Cole Younger was?

- Jesse James was not the leader of the James-Younger Gang, but to this day he is the most well-known member of the gang. He often wrote to newspapers about the gang’s exploits. Why do you think he did that? How does the public image of a person or a group affect our understanding of its history, influence, and truth?

- Why are criminals and outlaws like Jesse James so popular in our culture? Think about how they are represented in American society – in dime novels, movies, and more. How does this affect our understanding of historic events? What can we learn about historic events through historical fiction?

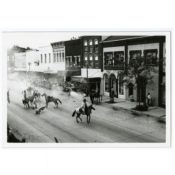

- Northfield became famous for this bank raid. The city began performing reenactments of it in 1948 for a festival called the “Jesse James Day”. Now, the reenactments are more historically accurate and the festival is called the “DEFEAT of Jesse James Days.” Why did they make these changes? How well does the reenactment tell the story of what really happened? What messages does the Defeat of Jesse James Days festival spread?

Related Items in the Northfield-Rice County Digital History Collection

Cole Younger’s account of the Northfield robbery

Excerpts from the First National Bank of Northfield, Minute Book #1 – including time-lock information

Documents about the James-Younger Bank Raid from 1876

Eyewitness Recalls Attempted Bank Robbery by Jesse James – Maude Ordway, 1966

Funeral Discourse of Joseph Lee Heywood

Historical Memories from Ira Sumner’s Daughter

The History of The First National Bank of Northfield, Minn. (especially page 3)

Indictments of the State of Minnesota against T. Coleman Younger and J. and R. Younger

Inventory of folders in the Jesse James Drawer of the Northfield Public Library

James-Younger Gang Bank Raid online collection guide with links to the Northfield History Collaborative’s full digital collection

James-Younger Gang newspaper accounts

The Northfield Bank Raid – a radio talk by Carl Weicht

The Northfield Bank Raid 50th anniversary publication

The Northfield Raid, published by the Northfield News in 1933

The Northfield Robbery, by William Pye for the Rice County Historical Society, 1947

Post-Raid Count of Money in the First National Bank made the day after the bank raid

A Thrilling Event in the Life of Mr. A. E. Bunker, from the Buckeye Informer, Nov. 15, 1896

“Webster Man Gives His Story of James-Younger Raid” – account of A. O. Sorbel, who reported on the gang in Madelia

Additional Resources

Boggs, Johnny D. “The Great Northfield Raid Revisited: New research that changes our understanding of the James-Younger debacle.” True West Magazine, August 6, 2012. Web (accessed June 20, 2018).

First National Bank of Northfield collection. Northfield History Collaborative. Web (accessed May 23, 2018).

Gardner, Mark Lee. Shot All to Hell: Jesse James, the Northfield Raid, and the Wild West’s Greatest Escape. New York: William Morrow, 2013.

Gale Family Library. Research guide for the Northfield Bank Raid. Web (accessed May 10, 2018).

Koblas, John J. Faithful Unto Death: The James–Younger Raid on the First National Bank, September 7, 1876, Northfield, Minnesota. Northfield, MN: Northfield Historical Society Press, 2001.

Koblas, John J. Minnesota Grit: The men who defeated the James-Younger Gang. St. Cloud, Minn.: North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc., 2005.

Minnesota State Archives finding aids to records about the Younger Brothers’ guilty plea, time in prison, and the court records of State v. Younger Brothers. Available online (accessed September 11, 2018).

Moore, Leslie. “Northfield Bank Raid.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. Web (accessed May 10, 2018).

“Northfield’s Sensation.” Minneapolis Tribune, September 8, 1876. Available online (accessed May 23, 2018).

Northfield Bank Robbery of 1876: Selected Manuscript Collections, [c.1880]–1962. Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul. Web (accessed May 10, 2018).

Smith, Robert Barr. Last Hurrah of the James-Younger Gang. University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Topics on Chronicling America – The Fall of Jesse James and the James-Younger Gang. Library of Congress historic newspapers. Web (accessed September 5, 2018).

Primary Source Analysis

Here are some tips for analyzing the primary sources found above and throughout the Collaborative. For each source, ask students to indicate:

- the author’s point of view

- the author’s purpose

- historical context

- audience

For inquiry-based learning, ask students to:

- explain how a source tells its story and/or makes its argument

- explain the relationships between sources

- compare and contrast sources in terms of point of view and method

- support conclusions and interpretations with evidence

- identify questions for further investigation

Additional Tools

- Document Analysis Worksheets from the National Archives

- Teaching with Primary Sources Videos and Sets from the Minnesota Historical Society

- Using Primary Sources from the Library of Congress

Minnesota Education Standards

Here is a list of education standard codes for benchmarks that can be explored using this Primary Source Set.

- 0.4.1.2.1

- 1.4.1.2.1, 1.4.1.2.2

- 2.4.1.2.1

- 3.4.1.2.1, 3.4.1.2.2

- 5.4.1.2.1, 5.4.1.2.2, 5.4.2.3.1

- 6.4.1.2.1

- 7.4.1.2.1

- 9.4.1.2.1, 9.4.1.2.2

- 1.8.7.7

- 2.8.7.7

- 3.2.7.7, 3.6.2.2, 3.6.7.7, 3.6.8.8, 3.8.2.2, 3.8.7.7, 3.8.8.8

- 4.2.7.7, 4.6.2.2, 4.6.7.7, 4.6.8.8, 4.8.2.2, 4.8.7.7, 4.8.8.8

- 5.2.7.7, 5.6.2.2, 5.6.7.7, 5.6.8.8, 5.8.2.2, 5.8.7.7, 5.8.8.8

- 6.12.1.1, 6.12.2.2, 6.12.4.4, 6.12.7.7, 6.12.9.9, 6.14.2.2, 6.14.7.7, 6.14.8.8

- 9.12.1.1, 9.12.2.2, 9.12.4.4, 9.12.7.7, 9.12.9.9, 9.14.2.2, 9.14.7.7, 9.14.8.8

- 11.12.1.1, 11.12.2.2, 11.12.4.4, 11.12.7.7, 11.12.9.9, 11.14.2.2, 11.14.7.7, 11.14.8.8

Send us feedback about this primary source set.

This publication was made possible in part by the people of Minnesota through a grant funded by an appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. Any views, findings, opinions, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the State of Minnesota, the Minnesota Historical Society, or the Minnesota Historic Resources Advisory Committee.